February 18th 2018

So, what have I been doing for the last year, since retiring as a globe-trotting cycling photographer and settling down to a quieter life? The answer, aside from the obvious ones of relaxation, reflection and lots of bike-riding is producing a book. In fact, producing a massive book, an 11 x 11-inch, 228-page, 330 image edition that reflects my forty years' long career. Creating the title was the easiest part of the book - 40 Years of Cycling Photography speaks for itself. The rest was not so easy, but was very pleasantly time consuming. Images had to be sourced, names and dates put to races and faces - and cross-referenced to make sure they hadn't been seen in any other recent books. Then the writing began, about 1,500 words per chapter to form some order to the book. Finally, and perhaps the hardest part, was working with the designer to ensure that only the very best imagery was in evidence after a series of editing sessions had whittled down the number of images we could squeeze in. The 330 images actually featured would have been cut from an original selection of several thousand, and only after several culls had been made. Oh yes, and then came the photo-captioning, hours and hours' worth, lovingly written and intended to offer full disclosure about why the shots were taken and why they were included in the book.

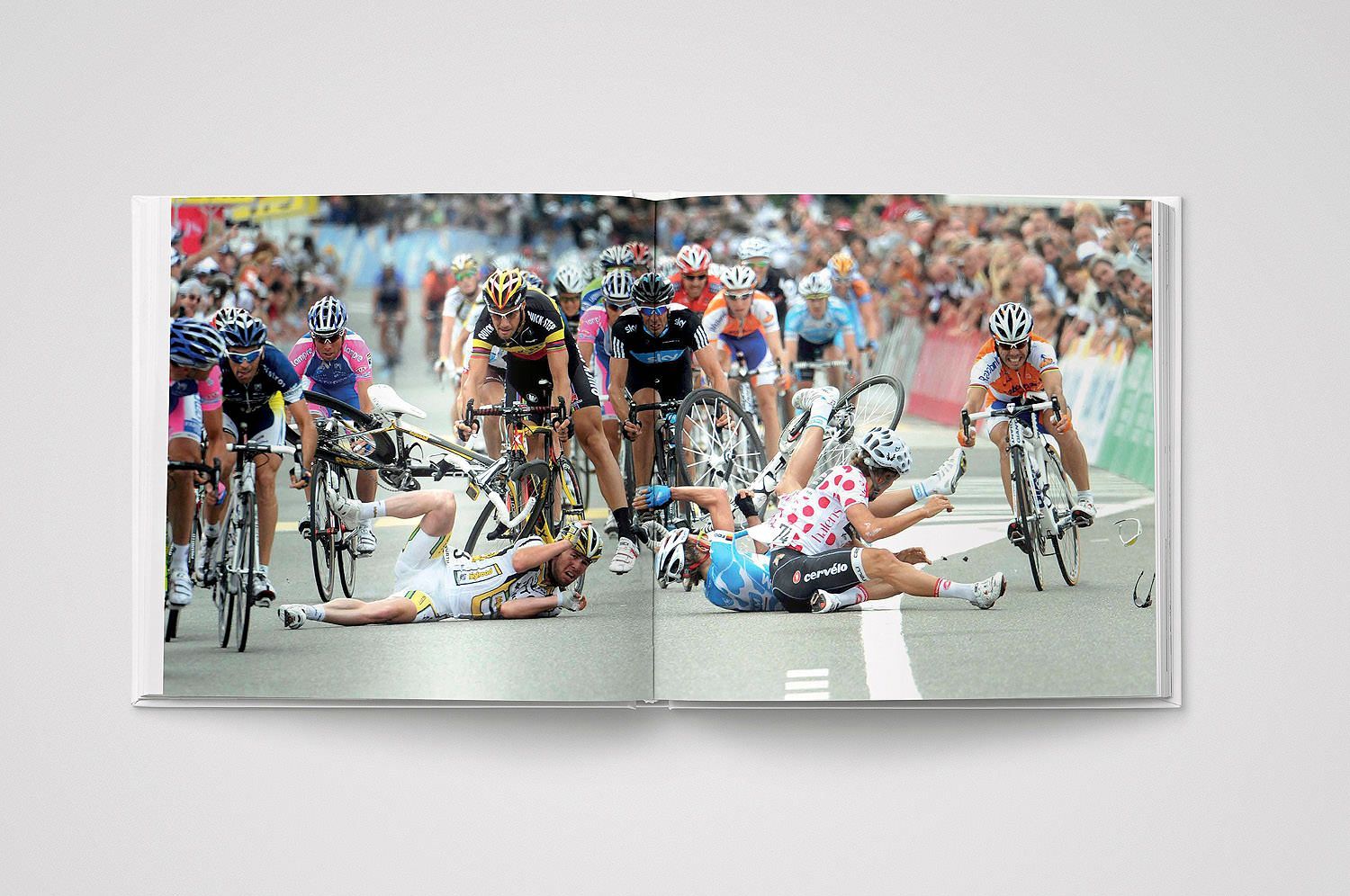

I gleaned an awful lot of satisfaction as I wound my way through everything I'd seen and recorded with my cameras since 1977 - the year I first set eyes on the Tour de France, and where I captured an image of Eddy Merckx that sent me on my way to having the greatest job in the world. So many forgotten images triggered so many long-lost memories, and helped me to collate some amazing stories for the book, both through long dialogue, short tales and those lovingly-written captions. The result is a volume of work that accurately represents what I once did and loved so much, and that I now want to share with everyone. There have been previous titles by me, led primarily by 'Visions of Cycling' which was published in 1988 and showcased the world of cycling photography for the first time. '20 Years of Cycling' was published in 2000 and could be said to be the little brother of this newest book. Yet 40 Years of Cycling Photography is a far deeper, richer, volume of work that covers twice the history of its sibling and a whole lot more in terms of content. This being a self-published project, so with no budget-watching publisher to wrestle with, I have been utterly reckless in ensuring the content covers far more ground than any previous book did. Cyclo-cross, track, road-racing, big races, small races, crashes, fun & games, Hour records, Olympic races - you name it, this book has it amongst its many pages, all under one roof, so to speak. But I won't spoil the fun of you actually seeing the book for yourselves by saying much more about the content.

Forty years is one huge chunk of a person's life, I now realise more than I ever did before. In navigating through my archive, I found it both fascinating and entertaining to run a parallel check with real history, to see where certain races or happenings sat alongside those of a bigger spectrum. When Bernard Thevenet won that 1977 Tour Jimmy Carter was President of the USA. Thevenet's victory preceded by just one month the death of Elvis Presley and came about one month after the first-ever Apple computer went on sale. I cannot imagine life as a photographer without my Mac to help me! Similarly, landmark events in cycling paired with so many significant parallels. The Chernobyl nuclear explosion in the Ukraine preceded Greg LeMond's first-ever Tour de France win in 1986. And when Greg won his second Tour in 1989, it was just over three months before the fall of the Berlin Wall. Just a few days after LeMond won the 1990 Tour, Saddam Hussein's troops invaded Kuwait, inciting the response of allied forces in an operation called Desert Storm - the pre-cursor to the Iraq War. Desert Storm - not LeMond's fourth win - contributed to the resignation of Margaret Thatcher as the UK's Prime Minister in 1990. And when Tony Blair ended his long reign as UK leader in 1997, Jan Ullrich was one month away from winning the Tour de France; tragically, Princess Diana was weeks away from dying in a car-crash in Paris. Though quite in-significant at the time, the world-wide-web was created in 1989 and operated for the first time in 1990 - now what a life-changer that was!

Still, there was plenty going on out there in the real world. The IRA began destroying its weapons in Northern Ireland in 2001, just months after Al Qaeda terrorists had destroyed New York's twin towers in what became known as '9/11'. This was the year that Oscar Friere won the second of three world road titles in Lisbon. In 2002, as Mario Cipollini won the worlds, and after Paolo Savoldelli had won the Giro, and Lance Armstrong his fourth Tour, the first-ever Euro notes and coins hit the streets of twelve European countries. 2004 saw Magnus Backstedt win Paris-Roubaix, Damiano Cunego rise to fame by winning the Giro d' Italia, and Roberto Heras win a third Vuelta in Spain. But the year ended in misery when over 250,000 people lost their lives in a massive Tsunami that hit the coast of Sumatra in Indonesia. By 2005, a start-up company called YouTube had begun broadcasting on the internet - it showed segments of Lance Armstrong's seventh Tour win that July. 2006 saw Floyd Landis win the Tour, only to be disqualified for a doping infraction less than a week later. 2006 was also the year when North Korea conducted its first-ever nuclear test, when Saddam Hussein was tried and executed, and when Paolo Bettini won the first of two world road titles in Salzburg. 2008 saw the world's financial markets crash - and badly. But it didn't stop Alberto Contador celebrating his first-ever Giro win, nor Carlos Sastre his only-ever Tour success.

And then came the return-and-downfall of Armstrong. His confession to doping in January 2013 caused a world-wide tremor, watched by millions on TV. But it wasn't anywhere nearly as important as other 2013 happenings like the Boston marathon bombing, or the devastation of Hurricane Katrina in Louisiana. Today's cycling champions have won in a world no less volatile. Carlos Betancur won a 2014 Paris-Nice overshadowed by the news that a Malaysian Airlines plane had gone missing over the Indian Ocean on March 8th; another Malaysian plane was blown out of the skies a few months later, just as Vincenzo Nibali claimed his Tour de France win in Paris. The little-known Miguel Angel Lopez won the 2016 Tour of Switzerland, just a week after the death of ex-boxer Muhammed Ali, the greatest sports personality of all time. And in 2017, Donald Trump was sworn in as the 45th President of the USA on January 20th, the same day Caleb Ewan won stage four of the Tour Down Under, just days before Richie Porte won the race overall and I stopped working as a photographer. Sorry for the long yarn, but it's quite amazing to see how forty years of cycling history went by in parallel with more-worldly milestones. It also means my career ran not just from Eddy Merckx to Richie Porte - it also transcended nine Presidents of the USA, seven British Prime Ministers, or - if you like - thirty-two Italian Prime Ministers!

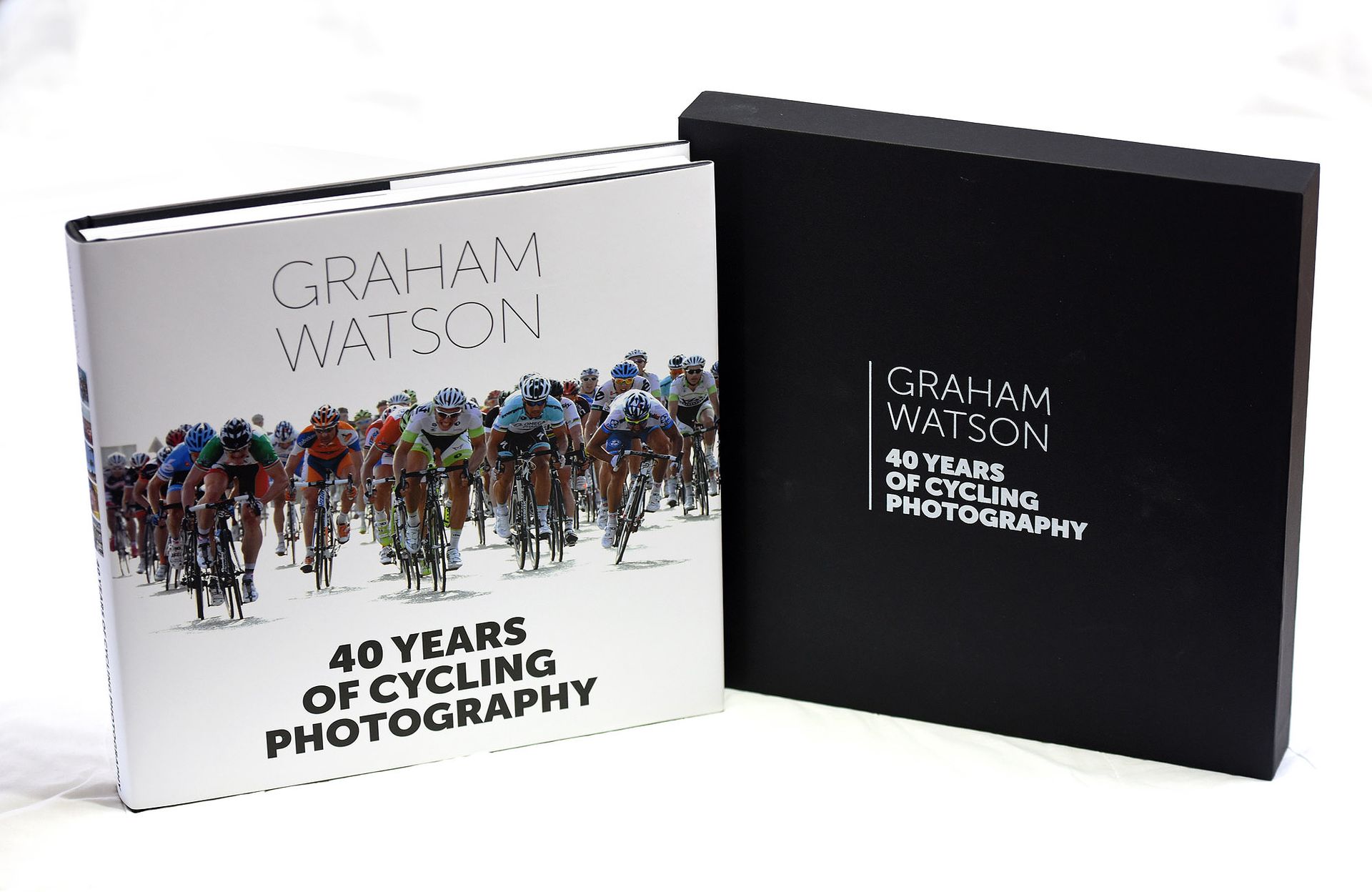

So, let's start at the front shall we - with the cover. How do you choose the cover shot for a book of such historical longevity and generational expanse? And from a sport so colourful, beautiful, and so full of variety? When do you choose the cover shot? In fact, we put a few options on to the designer's table early-on in the production, then let them ferment and percolate a while as the main body of the book grew. The cover shot then came down to three choices: a generic scenery shot, a generic action shot; or one of my classical shots from the not-so-recent past. We opted for a sprint shot because of the dynamism of the sprinters going for the line in a stage of the 2011 Tour of Oman. The timeless nature of the shot and the energy within it caught our eyes the most. That and the bleached-out background which made virtual silhouettes of the cyclists. The white-out and black shadows also formed two design elements of the book, at least as far as the hard-cover board and slip cases are concerned. A dramatic cover is considered by many people to be the most important element when selling a book. I don't disagree, but also consider it as just that - a cover, sometimes never to be looked at once the reader opens the first few pages and is drawn into the main body of the book. Still, it is the first time one of my books has had a sprint shot as the cover.

I couldn't put a book like this together and not pay homage to the many thousands of cyclists who've enriched and, literally, enabled my career. How many cyclists did I actually photograph between July 1977 and January 2017? Just a few dozen 'stars shine out from the rest for their achievements, or because of their unique character and, even, friendship shown towards me. Just two of those greats, Sean Kelly and Cadel Evans, play a special role in the book. Kelly, born with an insatiable appetite to win and a steeliness and physicality that photographers fought so hard to capture, was omnipresent throughout the first half of my career, winning just about every race there was to win except for the Giro, Tour and Worlds. Kelly wrote the Foreword for 40 Years - there were no other contenders for the job. He alone had the right qualifications. Evans represents the latter part of my career, a man who won races like the 2009 World road championships and the 2011 Tour de France, but who fought tooth and nail to win a whole lot more as well. If I saw Kelly win from the very word go, Evans' biggest wins were a long time coming, yet he never gave up trying - he became a champion more because of hard work, a perfectionist who, like all such individuals, had to wait a little longer for his successes. Cadel wrote the Afterword for the book, a more perfect accompaniment to Kelly there is not. Together in the book, they made a sandwich out of me…

One of the more surprising elements of this new book was how hard it was to squeeze everything in. Originally planned to be 216 pages, I went for a deluxe upgrade to 228 pages in order to get more imagery in - and it was still barely enough. I wanted at least one huge scenery shot from all my favourite races - but discovered that I had too many favourite races. So competitive was that area of the selection that only in the last days of production was I able to squeeze an Alpine shot of the Dauphiné-Libéré in. The action shots were even harder to whittle down. I envisaged getting half-a-dozen images of Bernard Hinault into the book - the first five-time winner of the Tour I'd photographed. In fact, the book contains just three images of Hinault. The most recent winner of the Tour, Chris Froome, fared no better in the book than Hinault, so it's not even a generational thing - there was simply too much other content to consider. Even winning a single grand tour or a big Classic didn't guarantee inclusion, it merely put that cyclist into the hat for the possibilty of inclusion. In the last chapter, I'd wanted to feature 15-20 'Legends', only to be told by the designer there was room for just ten. Ten! What can I do with just ten legends when I've photographed hundreds? As someone whose been around for so long and made a lot of friendships out of my subjects, I might have a bit of apologising and explaining to do to those that missed out on a tribute. .

The only way to cover so much ground was to run the book in chronological form. This was better for my sanity in that I had to think a little less hard about everything I'd seen and photographed and think more about how the pictures could be used. So many races, so many winners, so many stories - to not bag it altogether as one long passage in time would have been nigh-on impossible. There's an ebb and flow to each chapter as the cycling greats first emerged, then dominated, then gradually melted away into the shadows as newer winners rose up. And as a multitude of careers merged or diverged, so did my observations of the sport grow too. When I first began following races in the late-1970's I was like a headless chicken running around snapping away at anything that moved. Ten or fifteen rolls of film per day was the norm' in the biggest races. Twenty years on, a lot less 'film' was shot as my discerning maturity allowed me to anticipate where the best images would come from. And although the seven chronological chapters are bound by father-time, there's an awful lot more to those years than mere racing or scenery. The joys of winning, the sadness of losing, the pain of crashing, the thrill of escaping - yes, these are all fundamental emotions forever linked to the sport. But alongside these images come much more. Think of humour, of daring, of friendship, and even showmanship - the photo-editing of these decades was fun all the way!

If chronology helped my image-choosing more than a little, the same could not be said for the images I've snatched around the actual racing. There was a time when I felt that a full season was one that saw me going to a few early-season races, then the Classics, then the Vuelta, Giro, Tour - and finally the Worlds. With perhaps an autumnal gem like Paris-Tours or Lombardy to indulge myself with as the season closed. But newer non-European races came along in the early 2000's, enticing me to other parts of the world and inspiring a whole new archive of images. This was where my picture selections for the book got that much harder. Modern races like the Tour Down Under, the Tour of California, Arabian events like Qatar, Oman, Dubai and Abu Dhabi - and even Australia's Herald Sun Tour - brought increased competition to the picture selection. Equally, any race - old or new - has a character that is unique to that race, an attraction that cries out to be caught on-camera and maybe published in the book. This is never truer than with the Olympic Games, a sporting colossus I photographed seven times between 1992 and 2016. Needless to say, I've made special sections for each Games. The imagery of those events is too good to be excluded and reflects the titanic battles between the old Germany, France, Australia and Great Britain as they set about dominating the cycling world.

But this is not just a book about the sport of cycling between 1977 and 2017. It's a descriptive about the life that comes with such a job, a highly adventurous one at that. When I first saw a full Tour post-1977, it was thanks partially to the old steel F.W. Holdsworth bicycle that carried my hulk and camping gear around France. Not to mention my cameras too. Sometimes with the help of an old Ford Escort or sometimes just solo on my bike, I'd pick off as many stages as I could get to in three weeks. And as the sales of photos increased, so did the car became the sole mode of transport, to be up-graded to a moto in the mid-1980's. In more recent times I've been the 'key man' photographer in a team comprising a moto-driver, car-driver, and faithful assistant. In the late-1970's I'd take a train and a ferry to get to France, and then hitch-hiked if I had to - I think it took until 1983 before I ever flew to a race. Then, flying became a near-daily event in the mid-1990's and took me all over the world to races in the Philippines, China, Mexico, Australia and Colombia - the adventures I had on those trips were unforgettable, and are included in one chapter devoted to travel. Because of the day-to-day upheaval of moving on to a different town or city, the lifestyle of a cycling photographer is quite unique, yet still something to enjoy and savour - and share with the reader too.

Likewise, my forty years in the job saw a complete transformation of camera gear and technology. There was not one single digital image in 'Visions' or '20 Years', and the publisher's greatest costs were probably turning my slides or black and white prints into pre-press film - lots of it. That 1977 image of Eddy Merckx was shot on a roll of grainy Kodak film and has since been digitalised with the rest of my film archive. Symbolically, it is the very first image inside '40 Years'. The most recent images were taken on a state-of-the-art Nikon D5, using a technology that allowed me to transmit images directly from the camera. Photography has evolved a lot since 1977, and no book about photography in the 21st century would be complete without detailing the time-line to where we are today. An old wooden Kodak camera I lived off in the 1970's was replaced by a first-ever SLR camera as the addiction to cycling took hold. Cameras and lenses were added or taken away, but upgraded as often as I could afford. I used to love the winter because with little or no travel expenditure to consider, every pound or dollar I earned went on buying the latest gear. Incredibly, I kept a large proportion of those old cameras - primarily because some were so badly worn or damaged that they were un-saleable anyway! Which is why, at regular intervals in the book, you'll find an occasional side-bar to describe that era's choice of camera and accessories.

Having enjoyed the privilege of getting many books published down the years - the first being 'Kings of the Road' co-authored with Robin Magowan in 1986 - I have self-published this one. Gone are the days when book-distributors looked the other way when individuals like me came along - the internet has changed the way books are sold and marketed. Gone too are the long and expensive production lines where designers pasted sheets of typeset paper onto dummy pages and then used translucent tape to stick down prints or slides alongside those sheets of text - computers with clever software do all that now. More importantly, the printing process has changed wholesale, with no requirement of reprographic film or 'plates' prior to printing. Just a set of PDF proofs to admire, to critique, and finally to approve. This used to be called 'straight to press' - from computer to paper - but is now popularised as desktop publishing. So less financial risk, greater control over the final product - it is the latter aspect that tempted me to go for self-publishing, and granted me no-end of control over my work. When you're spending your own money, you can choose exactly which images you want in and how they'll look once they're in. Not for me a fight with a publisher on content - this one final book has my absolute stamp of approval on it. If not exactly a labour of love, it is at least the defining book of my career.

So how did it feel when the first-ever printed and bound book landed on my doorstep in late-January? Relief for one - that the hard work was over and there was finally something to show for it. Until I'd actually got my hands on a copy of the book, it was easy to believe it was never going to happen - like a dream that hadn't come true. But there it was, shrink-wrapped and boxed-up to survive the journey from China. This particular book came inside a sleek black slip-case for added presentation, forming a collector's item that we'll soon be offering to a few lucky people. The cover was studied for its delicate colour balance - were the shadows too dark? No - nor the road too washed out. Let's turn the pages now: how did that black and white shot of Eddy Merckx turn out? And how was the first scenery shot of the book, a double-page Alpine beauty from 2009 - delicious! And then came the guts of the book, page after page of cycling champions past and present, each of them fighting to win, or fighting very hard not to lose.

One of my first reactions when I opened the book was how the drama and beauty of the sport have been a constant companion since 1977. Throughout the volume of work there's not one spread of images that doesn't have a highlight, a sparkling gem, a mouth-watering panoramic or a stomach-tingling crash shot. And I don't mean because of my photography - I can only photograph what is actually there. And there's an awful lot out there. Nostalgia can be seen fighting with modernism as old steel bikes were replaced by titanium or early carbon frames. Bare heads were about to be capped by hard-shell helmets, and wool had already surrendered its trusted values for Lycra. I especially enjoyed the older images of cyclists actually having fun in their daily workload - and that's just for starters. I allowed myself to enjoy a wave of emotion as the pages turned, as the memories passed, as the colour and drama flowed before my eyes. Did I really take all these pictures, I found myself asking? Well, yes, I did… And then before I knew it, those 228 pages had been turned in full for the first time.

Well, hopefully, I've whet your appetites just enough without giving away too much of the book's content. I'm confident to state it's the most complete photo-book ever produced by one single cycling photographer. It is both a pictorial encyclopaedia of the last four decades of the sport as well as a tribute to the cyclists and races that formed the heartbeat of those decades. I've made sure to include many of my classical images in the ten chapters, the ones that really excited me or that reflected the sport at a particular date in time. I've also dug deep into the archive to offer an absolute ton of unseen imagery, in black and white and colour. 40 Years of Cycling Photography goes on-sale around mid-March, and will be stocked at our on-line stores in the UK, USA and New Zealand for a faster worldwide service. Go to www.grahamwatson.com/pages/store and then click on your nearest national flag. For those wanting something a bit more special, we're offering 30 signed books with slip-cases - a great way to display and protect the book on your desk or book-shelf. These slip-cased, signed books, can be dedicated to colleagues, friends, or directly to yourself, if you so wish. The slip-cased books come at a premium price because they weigh a lot more and have to be despatched from our base in New Zealand. We'll ship you the books but we're keeping the sunshine, fine wines, exquisite scenery, and unique culture to ourselves..!

Share this article

Recent Posts